Art, Tea, and Culture: A Journey with Pierre Sernet

Imagine a tea room that travels the world, setting up in different corners of the globe to bring people together. This is the heart of Pierre Sernet’s project, “One”.

In “One,” Pierre captures the intimate moments of sharing tea with strangers from different cultures and countries. His portable Japanese tea room transforms any setting into a serene space for connection and conversation. Pierre’s project invites us to see beyond our everyday surroundings and explore new cultural perspectives.

Through the simple act of sharing a cup of tea, Pierre highlights the mankind’s universal need for connection. It reminds us that no matter where we are from, we share common values and experiences.

When I first met Pierre Sernet and saw his project One, I was immediately drawn in. The concept is beautifully simple: Pierre’s work is a celebration of the human spirit, and I felt an immediate sense of purpose in wanting to share this project with the world. His message is simple but incredibly meaningful, One shows that through the simplest of moments, we can find a sense of unity and understanding.

Get ready for an exciting conversation as I sit down with Pierre Sernet, the creator of One, for an exclusive interview..

Hadi Brenjekjy: Hi Pierre, it’s awesome to have you here today. Let’s jump right in!

Could you share a bit about your background and what led you to where you are today?

I was born in 1951, raised, and educated in Paris. I was brought up to appreciate all forms of art. As a boy of ten, I collected art posters that stores, in those days, would place on their doors to advertise museum and gallery shows.

At the age of eight, I studied drawing and pastel in a studio. I had to draw still lifes, but I was much more interested in the nude models that the adults were drawing. Later, I started working in photography to make pocket money.

I went to business school, and in 1973, I decided to visit America for a couple of months to better understand how business was conducted there.

By accident, I ended up working for a large commercial bank for five years. Then I left to set up a computer hardware company and continued as an entrepreneur. I ended up staying in New York for 43 years.

I developed an interest in Japanese culture in my late twenties and eventually studied the tea ceremony for 16 years in New York, where the Urasenke School of Tea has an amazing set of tearooms in what used to be Mark Rothko’s studio.

I moved to Japan full-time in 2019.

Your career spans photography and business before you ventured into your current role. How did your experiences in these fields shape your transition to what you are doing now?

As an entrepreneur, you experience both success and failure, but hopefully, you always keep learning.

In 1985, I collected 19th-century Japanese photography. At that time, the art world had no easy way to find or evaluate art being offered for sale. I believed there was an opportunity.

In 1986, I started what was later renamed Artnet, to display images of what was coming up for sale at 177 leading auction houses worldwide. We created the first image database in the world, and it became a showcase for Intel and IBM technologies.

At the time, I asked auction houses to grant me a 49-year exclusivity for their electronic images. Over one hundred agreed, and seventy-seven gave us exclusivity ranging from 2 to 35 years. No one had ever seen digital images before. Artnet was a major disruption in an industry accustomed to photographic transparencies and directories listing art values without any images.

I’ve always believed that if there’s a need, there’s an opportunity, and you should never take “no” for an answer.

It’s often easier for people to say no, or that something won’t work or is impossible. But if you believe in it, you can make it happen.

I went on to set up more than ten different ventures across fields ranging from computer hardware, software, and manufacturing to databases, internet polling, and real estate. Many were firsts in their industries. Some succeeded, and many did not.

Business is a form of creativity. One should never be afraid to try.

The tearoom concept you have developed is intriguing and culturally rich. Could you elaborate on its origins and how it reflects your broader vision?

The tea ceremony is based on four principles: harmony, purity, tranquility, and respect.

As an art form, it requires knowledge of nearly every Japanese art form except music. You must know about garden design, architecture, history, poetry, religion, painting, calligraphy, incense, flower arrangement, lacquer, ceramics, food, and, of course, the different procedures for making tea.

Learning the tea procedures is difficult, but mastering all these other art forms is even more challenging. However, the most difficult part is living with the spirit of tea.

After 16 years of studying tea and 25 years of making tea, and having a tea name, I know I will never master it. But it has strengthened my belief in respect, which I think is something our contemporary world has lost. I live in Japan because I feel respect is the foundation of its society.

At the start of the millennium, I noticed growing polarization through anonymous internet postings. After the 9/11 attacks, I saw the U.S. trying to impose its single-minded views on the world, which I felt reflected a lack of respect for other cultures and lifestyles. I decided to use art to express these feelings through my photographs.

Tea culture is indeed widespread, but Japanese tea culture is particularly unique. What drew you specifically to Japanese tea traditions, and how has this choice influenced your work?

Because the tea ceremony is unique and largely unknown outside Japan, I felt people would stop and pay attention when it was presented in artwork.

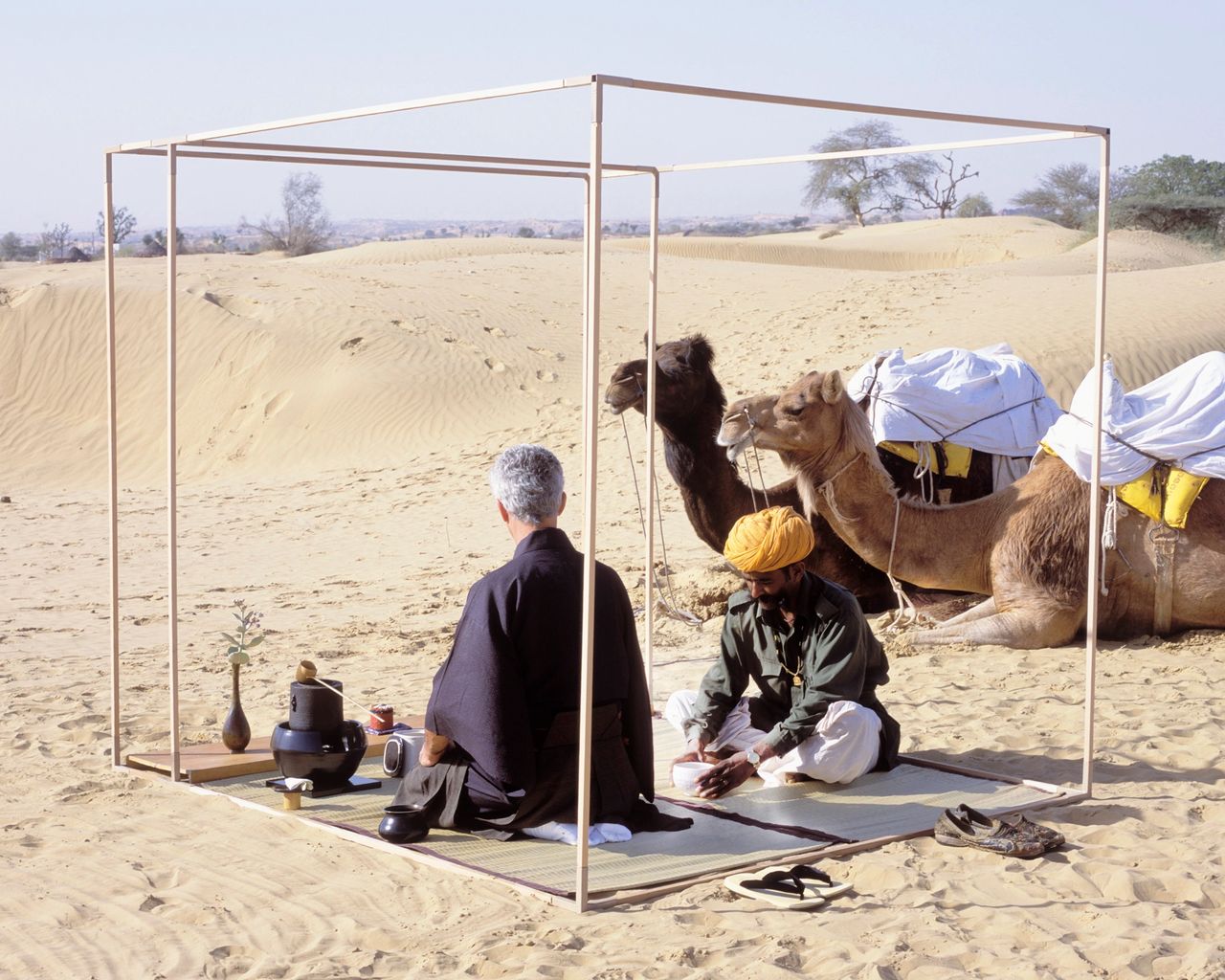

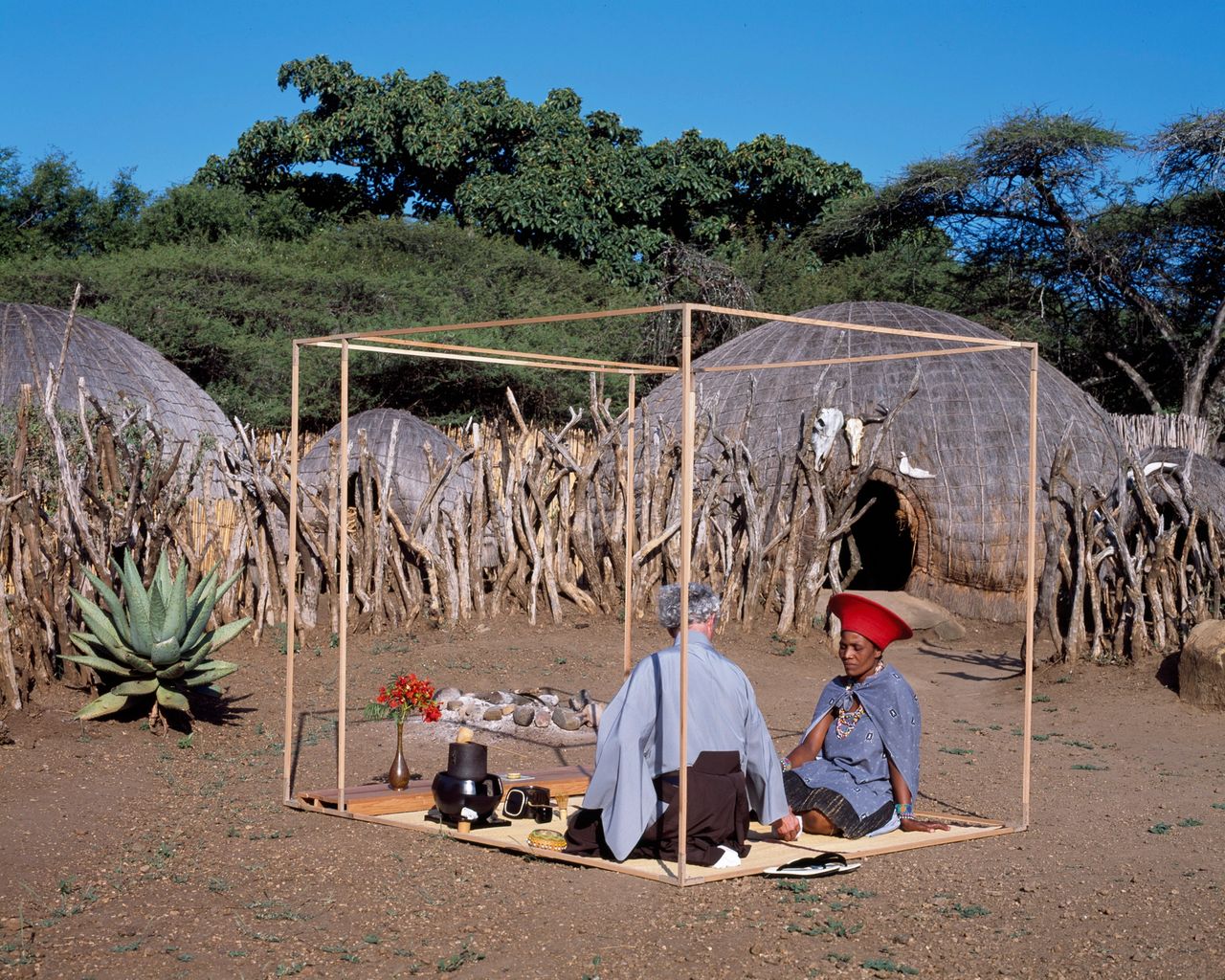

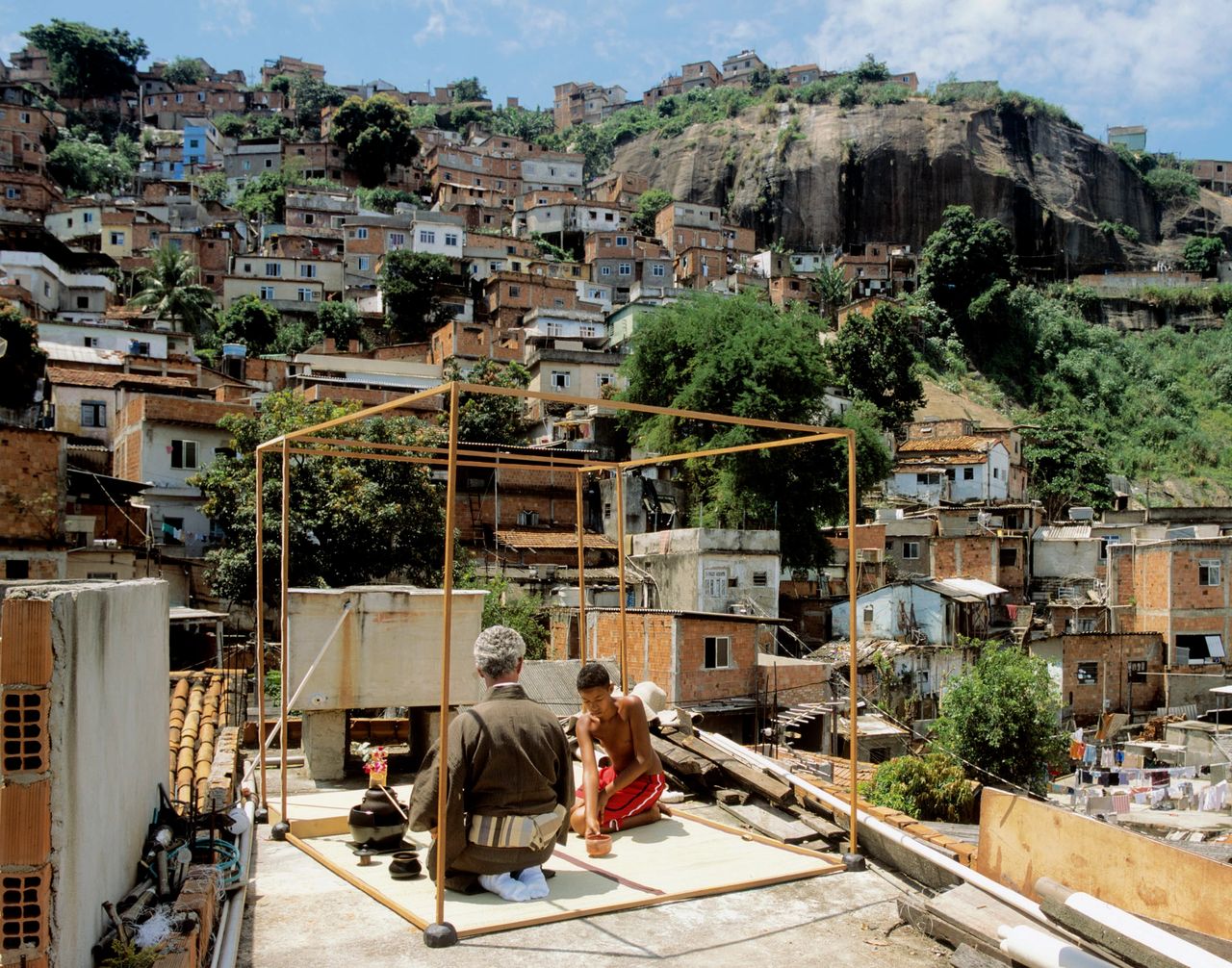

I created a portable structure that replicates a Japanese tearoom, which I can use to invite guests from all over the world, in their own environments.

The idea was to juxtapose seemingly incompatible cultures or environments by inviting viewers to place their own cultural, spiritual, religious, or philosophical values within the cube.

The goal is to show that, despite apparent differences, these worlds share similar universal values that can coexist.

Through the resulting photographic works, I sought to demonstrate the commonality of humanity across time and place.

I went on to create five other series exploring themes like faces, love, death, nationality, and sex to show how humanity treats these issues in similar ways across the world.

If you were to explore another culture besides Japanese, which one would you choose, and what aspects of it resonate with you?

While I live in Japan, I find countries with long-established cultures and histories particularly interesting.

France, among the old European cultures, is a place where all forms of cultural expression are accepted. I believe it will remain a culturally vibrant place.

The United States, of course, is also interested in culture, but it focuses primarily on contemporary culture. Understanding contemporary art doesn’t require deep historical knowledge, unlike understanding older art, like ancient civilizations or Old Masters.

People in “new cultures” are less exposed to historical influences compared to those in older cultures.

So, if I were to explore another culture, it would be France, especially Paris. As we saw with the Olympics, it remains the most beautiful large city in the world.

As we look to the future, how do you envision the relationship between art and culture evolving over the next decade?

That’s a subjective question. Today, art and culture mean different things to different people.

Historically, culture included music, fine arts, literature, theater, and dance. Today, in addition to those, we have many other avenues for artistic expression such as film, video, electronic art, and manga.

For me, fine arts are especially important in defining a culture. Think about it: does anyone remember the name of the U.S. president in the early 1960s or who led Germany in the 18th century? Yet everyone knows Warhol, Bach, or Picasso.

It’s likely that the Beatles or Taylor Swift will be remembered longer than Prime Minister Macmillan or President Biden, just as Leonardo da Vinci is emblematic of the Renaissance.

Can you share a particularly memorable experience or project from your journey, whether in art or photography?

While the photographs are the result of my tea ceremonies, sometimes the experiences themselves are the most memorable.

One instance was at Paris Charles De Gaulle airport. I was making tea for an airport employee in the middle of Terminal 2, watched over by two well-armed CRS officers. Suddenly, more officers rushed in, evacuating everyone due to a bomb threat.

I apologized to my guest for not being able to finish the tea. One of the CRS officers overheard me and said, “No, you stay!” Despite the bomb threat, my guest and I were the only people left in the empty terminal, sharing a bowl of tea. It was a surreal experience until a controlled explosion signaled that it was safe for people to return.

Another memorable experience was making tea in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. We needed an armed bodyguard to protect us as we moved around to take pictures, as it would have been too tempting for someone to steal our camera equipment.

In the favela, we also needed a “local bodyguard” to introduce us. After climbing through several homes, we reached a terrace where I set up my tearoom and camera.

While I’ve made tea for many people, one of the most memorable was a 14-year-old boy in the favela. He was more centered and focused than many professional tea practitioners I’ve met. He truly felt like a “chajin,” a tea person, even though he had probably never heard of the tea ceremony before or since.

Of course, not all experiences are as positive. While making tea on the Bund in Shanghai, a crowd gathered, and we were concerned about the local police. Shortly after we started, a police car appeared, it turned out we were on the roof of the police station! After spending the afternoon trying to explain our project to the tourist police, they didn’t seem to appreciate our tea values.

However, whether on gay beaches in Mykonos, with Zulu people in South Africa, farmers in Mexico, Buddhist nuns in Angkor, or camel herders in India’s Thar Desert, these tea encounters have shown me that, despite our apparent differences, we can share moments of connection and unity.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a business in the cultural or creative space?

First, consider whether there’s a large demand for your offering.

You may be interested in a particular idea or solution, but that doesn’t necessarily mean a large segment of the population will be. Ask people, listen to their feedback, and conduct as much market research as you can.

Check for competition. Are there others already entrenched in that market? Do you bring something unique, or is it easy for

others to replicate what you offer?

Most importantly, do you love what you are about to do?

However, if people dismiss your ideas but you still believe in them, go ahead and pursue them! It’s better to try and fail than do nothing and live with regret.

How do you stay inspired and continue to innovate in your field?

By staying curious, always learning, and looking for gaps in the market where there are opportunities. I also bring ideas from other industries and apply them to the art market.

I’m currently working on a completely new offering in the art market. While I can’t detail it here, if I can make it happen in the next five to seven years, it will be a first worldwide and is likely to have a notable impact on the global art market.

Thank you Pierre, for sharing your insights with London Intercultural Centre. We can’t wait to witness your next masterpiece!

Thanks a lot Hadi, for having me!